Accelerating genetic progress with embryo transfer

Veterinarian and beef farmer Dr Gerard te Lintelo is making rapid genetic progress to grow his Shorthorn herd.

“Breeding with average only produces average. The quickest way of getting to where we want to be is to constantly improve generations.”

- Dr Gerard te Lintelo

From the moment of its own conception to the point of putting a live calf on the ground, the genetic turnover time in cattle is around 2 years and 9 months – making genetic progress a strategic long game.

When Dr Gerard te Lintelo, a practicing veterinarian, purchased a farm on the on the outskirts of Wolsingham in Durham three and a half years ago, this prolonged period of genetic evolution was a major obstacle for his plans of developing a pedigree Beef Shorthorn herd.

“From the start, my plan has been to develop a base of pedigree genetics for commercial producers, focusing on traits like good feet, udders, efficiency, meat quality, fertility, calving ease and temperament,” says Dr te Lintelo. “I’m after producing profitable genetics for commercial beef producers.”

Dr Gerard te Lintelo and his son, William, work together to pregnancy detect recipient cows to determine which calves are natural service from the sweeper bull and which calves are from embryos. Recipients are scanned at 35 days pregnancy and then a sweeper bull is put in the same day.

After an initial purchase of five bred heifers, Dr te Lintelo decided to utilise embryo transfer (ET) to accelerate the development of his genetic base. Present day, his pedigree herd consists of 28 head of breeding females with plans to build it to around 150.

According to Dr te Lintelo, using ET to set up a herd has several advantages over using semen and/or natural service.

“With ET you have the ability to bring in top genetics from both maternal and paternal lines, whereas with using artificial insemination or natural service, this is limited to paternal lines,” he explains. “ET also takes down geographical barriers – allowing you to access the best of the best genetics from anywhere in the world,” he says.

Sourcing genetics from Australia and Canada, Dr te Lintelo says this has also helped improve animal performance.

“When it comes to a relatively closely linked genetic pool within a country, you can actually see internal heterosis when introducing new genetics from the same breed from unrelated lines. This goes on to contribute to offspring with more vigorous traits and improved health,” he explains.

Recipient cow management

While ET is an effective way to increase the genetic progress of a herd, it does not come without investment costs and risks. According to Dr te Lintelo, the average embryo costs £500 to purchase and averages a conception rate of 50% – not including vet and medicine fees.

Dr Gerard te Lintelo’s Arrowquip Q-Catch manual squeeze crush from Wise Agriculture allows handlers to operate the sliding rear gate and head gate at the same time, reducing labour requirements.

To maintain a profitable breeding programme even if an embryo doesn’t stick, risk is spread through the recipient herd. This starts with a careful evaluation of any recipient animals before they are enrolled into the ET programme.

“My recipients are Shorthorn and Angus crossbreds that have a good baseline of production genetics and high health status. Prior to entering the ET programme, I check their reproductive tract to ensure it is in working order.” he says. “Nutritional management of the recipient herd is also paramount, with cows receiving mineral boluses twice a year and the feeding programme consisting of high-quality grass and silage to maintain a body condition score of 2.5-3.0. Recipients also receive all vaccinations and anti-parasitic treatments prior to the start of the ET synchronisation programme.”

While these practices help to increase the embryo success rate, their quality genetics also act as an insurance policy.

“A significant hidden cost of any ET program is the delay in getting recipient animals in calf when the embryo does not hold. If an embryo doesn’t carry, it can be three to four months before the recipient cow is pregnant again. That amount of time and resource being put towards an unproductive animal quickly adds up,” he says. “I scan the recipients at 35 days pregnancy and then add a sweeper bull with the recipients the same day. So, rather than being left with an open cow, I will have most recipients in calf within 8 weeks after ET. These will then produce my next generation of recipients and male animals are sold as steers.”

Low stress handling

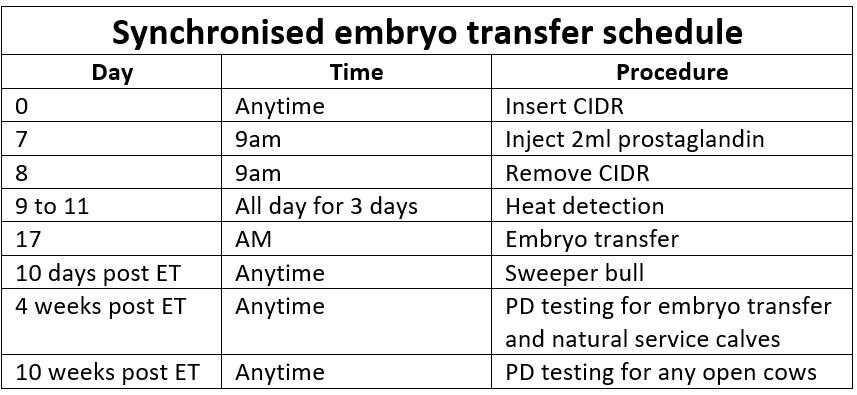

Currently, the operation is using a timed synchronisation protocol (see chart) that requires cows to be put through the handling system four times within 17 days. For peak fertility at ET, these processes must be done within specific time periods. Following ET, cows are put through the system two more times to detect pregnancy and to determine which calves are natural service from the sweeper bull and which calves are from embryos.

According to Dr te Lintelo, an investment into an Arrowquip cattle handling system, including a manual squeeze crush, forcing pen and race sections from Wise Agriculture that was designed to reduce stress and improve working efficiency has been essential to the success of carrying out the breeding programme.

“Stress cause by handlers and handling systems is detrimental to fertility and will cause a cow to either not breed or to abort her calf. And if cows don’t have a positive experience in the handling system, they will become sour and harder to work in the future,” he says. “Our Arrowquip cattle handling system was designed based on animal behaviour research, resulting in a very quiet and easy flowing system that allows us to accurately implement breeding protocols.”

Aside from the intense handling schedule as part of the breeding programme, the entire herd is handled regularly for performance recording, vaccinations, bolusing and TB testing.

“From a young age, we will run calves through the handling system multiple times without doing any procedures to get them familiar with it,” says Dr te Lintelo. “When we are doing procedures, especially if it is something unpleasant like being stuck with a needle, we will feed them some concentrate while they stand in the crush. Little things like this don’t require a lot of effort and go a long way towards reducing stress levels and improving their willingness to be handled in the future.”

Continuing genetic progress

As his herd numbers increase, Dr te Lintelo’s plan is to produce embryos from the top 20% of the females, with the bottom 20% going into his recipient herd. AI or natural service will be used for the middle 60% of the herd. Top performing bull calves will be developed and sold to pedigree and commercial producers for breeding, while culls are sold for fattening.

“Breeding with average only produces average,” he says. “The quickest way of getting to where we want to be is to constantly improve generations.”

This article originally appeared in the September 11th issue of Farmers Guardian and has been republished with permission.